AI Code Assistant SaaS built on GPT-4o-mini, Langchain, Postgres and pg_vector

Few months ago, I knew almost nothing about AI. I used ChatGPT and Co-Pilot (I'm civilized, after all), but a lot of the content around AI was Greek to me. Terms like models, transformers, training, inference, RAG, attention, and agents were unfamiliar. Last week, I have completed my first end-to-end AI-based product: AI Code Assistant. It is a tool for exploring new code bases by chatting with a virtual “senior developer” who is deeply familiar with the code. In the journey to build a full-fledged AI product, I learned a lot about AI - which I'm about to share with you.

In the previous blog in the series, we discussed core AI concepts - generative models, transformers, RAG, embeddings and a lot more. In this blog, I'll share how I built the AI Code Assistant. I'll cover the design decisions, the implementation details, and the gotchas I encountered along the way. You can follow along with the source code, and if you want to experiment with it yourself, you can sign up for a Nile account and create a free database for these experiments.

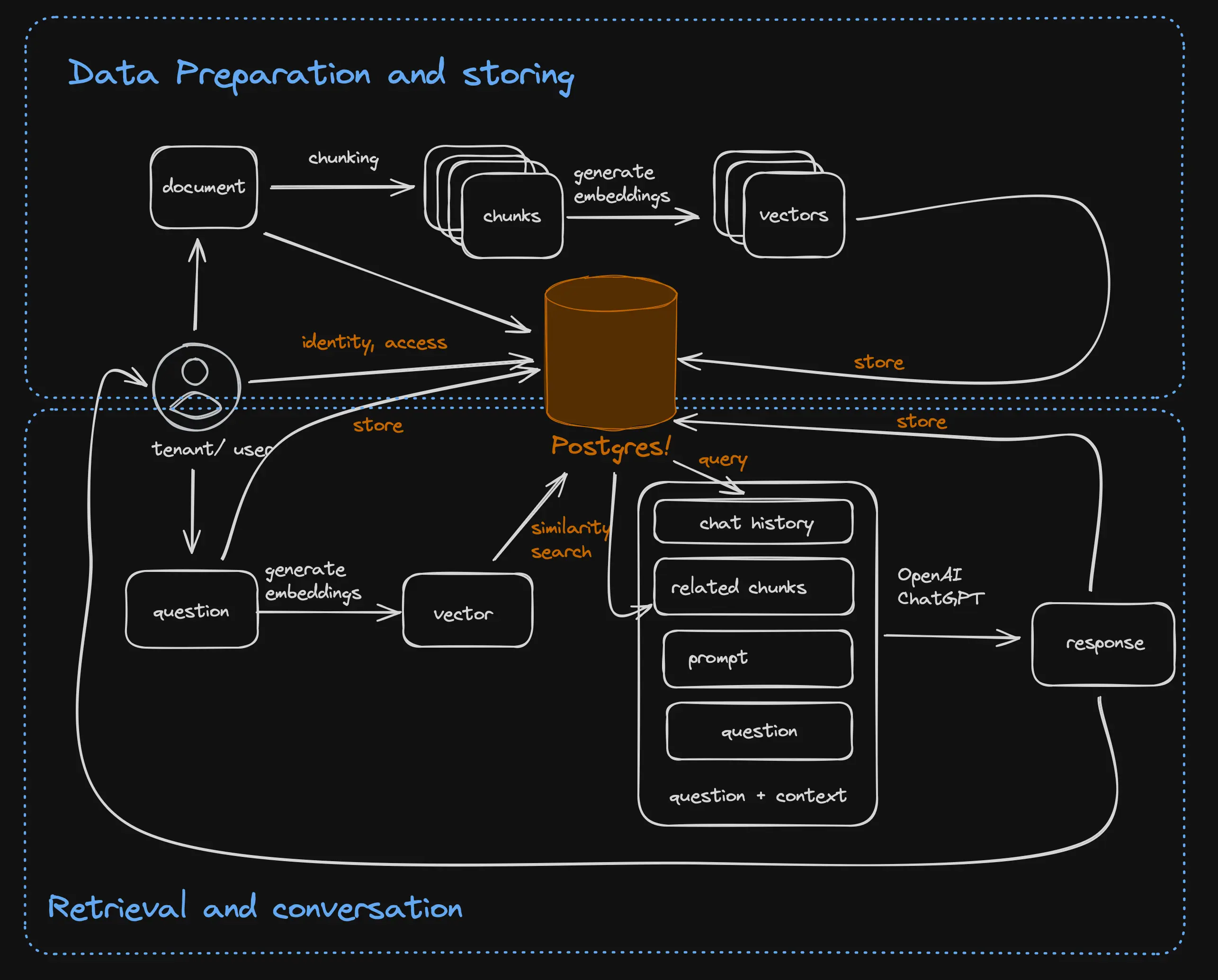

High level RAG architecture

As we discussed in the previous blog, I've decided to use RAG architecture for the AI Code Assistant. RAG architecture were a good fit for my requirements, which involved responding to user questions based on existing code-bases. Whenever requirements involve "use existing data in the model response", RAG is a good choice. Fine-tuning can be used in combination to help the model understand and perform better on specific tasks, and we may add it later. Starting with RAG allows you to get a good data set that you can later use to fine tune the model.

At a high level, all RAG-based architectures are the same. They have two independent phases:

- Ingestion phase: In which they load the source documents, split them into chunks, generate vector embeddings, store them in a database, and optionally generate an index on the stored vectors.

- Conversation phase: In this phase, they take the user question, generate a vector embedding, search the stored vectors for related chunks, and then send the question with the related text, conversation history, and a creative prompt to the model. When ChatGPT responds, the question and answer are stored and displayed to the user.

As you can see, the architecture uses LLM to generate embeddings and respond to user questions. It uses a database for literally everything else. You can see how the database is used not just to store the embeddings but also to store user identity, tenant information, and chat history. Which is why it is so convenient to use Postgres with pg_vector. In our example, we naturally use Nile, which provides extra capabilities around user identity and isolating tenant data into virtual tenant databases - including the embeddings.

The ingest and chat flows can be completely distinct. For example, in a customer support bot, there will be a process to update it with new documentation - this process is completely separate from the process in which it responds to user questions. Or they can be part of the same user experience in applications that let users upload their own documents and then ask questions.

In the Code Assistant architecture, I separated the ingest and conversation phases. Updating Code Assistant with new repositories is done from a small script in the command line. While interrogating the repositories is done from a SaaS-y web UI.

Within this high-level design, there are many details to consider. In this blog, we'll go over the application design from the ground up - from the database schema to the user interface. By the time you are done reading, you'll know everything you need to build your own AI Code Assistant, or similar RAG-based SaaS.

Data model

The data model is the foundation of the application. It determines how the data is stored, how it is accessed, and how it is updated. And naturally, it has to fit both the database and the application requirements.

As a database, we used Nile, which is based on Postgres, provides tenant-isolation out-of-the-box, and has the pg_vector extension built-in for storing

and retrieving embeddings.

Pg_vector adds the vector data type to Postgres, with vector distance operations, and vector indexes. You use it by declaring a table with a vector type. In our case,

this is fairly straightforward:

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS embeddings_openai_text3_large (

tenant_id UUID,

id UUID DEFAULT gen_random_uuid (),

file_id UUID,

embedding vector(1024) NOT NULL,

primary key (tenant_id, id)

);

Lets look at the design of the table.

Emebeddings table is tenant aware

You can see that the table has tenant_id column, which makes it tenant aware. The embeddings for each tenant are stored in their own virtual tenant database and

are isolated from each other. This has a couple of important benefits:

- Privacy: Each tenant's embeddings and data are isolated and won't get mixed up with one another.

- Performance: We only look for relevant embeddings within the virtual tenant data, a small subset of the entire collection and therefore faster to search.

- Scalability: As the set of embeddings grows, we can move some tenants to new physical machines, which allows us to use more memory and CPU for our applications over time.

Size of the embedding column

As you can see, we limit the vector size (or number of features) to 1024 dimensions. Different embedding models generate different vector sizes. Interestingly, there is very little correlation between the size of the embedding vectors and their quality. Models with 1024 or even 512 dimensions achieve comparable or better scores than models with 4096 and above dimensions in the HuggingFace leaderboard.

On the other hand, the size of embedding vectors matters a lot to Postgres. Postgres rows must fit in a single database block set when the DB is created. Typically 8KB. If a row needs more space, it is split up, and parts are stored in an overflow table. This behavior is called TOAST. Reading two rows (the original + overflow) takes longer than reading one. So, it behooves us to keep our vector size to 1536 or below. 2048 dimension vectors will already overflow.

Note that the size of the model has to match the size of the vector column exactly. You can't store 2048 dimension vectors in a 1024 dimension column, but you also can't store 1024 dimension vectors in a 2048 dimension column. Which brings us to the next point:

Embedding table per model

The table is called embeddings_openai_text3_large because the embeddings in it were generated by the openai_text3_large model. I experimented with several models and used

a separate table for each embedding. I used different tables and not a model column in each table because different models need vector columns of different sizes (as explained above).

And even if the embeddings of two different models have the same size, you still can't mix models - if you embed a question with openai_text3_large, you

have to search for related embeddings using the same model.

Because I didn't want to re-chunk and re-upload all the data when trying another model - I stored the code itself in a separate table.

Lack of vector indexes

After I embedded a collection of repositories for a few tenants for the live demo, I noticed that I have fewer than 100 embedding vectors per tenant. At this scale, vector indexes don't add much value (full scan of 100 blocks is plenty fast) but they add overhead and potential loss of recall. So, I skipped them for now. We'll have a separate blog post about vector indexes with appropriate examples.

Additional tables

Our model includes a few more tables for the documents and some metadata:

projectstable stores metadata about each repository we embedded - the tenant it belongs to, URL, and description.file_contenttable stores the actual code for each project and is linked to the embeddings table. So we can easily pull up the relevant code when we search for relevant embeddings (rather than make an API call to Github or S3 for each embedding).

When we get to the conversation phase, I'll show you how this data model allows me to find the relevant code snippets for a user question with a single query.

Choosing models and frameworks

When I started building the AI Code Assistant, I thought that the choice of both embedding model and conversational model would be a key decision. You can't have a good application if the models don't deliver good results. Then I realized that many models and model vendors share APIs, which means that I can switch models without changing the application (at least while the amount of data I have to re-embed is managable). And then I realized that it really depends - some model switches are easy, but some require deeper changes.

The criteria for choosing models:

- Quality: The model has to be good at the task. This is the most important criteria.

- Input tokens: I wanted to feed the model reasonable chunks of code, so I needed a model that can handle at least 512 tokens. But more was better.

- Dimensions: I needed models capable of generating embeddings with 1536 dimensions or fewer. Some models are based on Matryoshka Representation Learning, allowing them to scale down while maintaining most of their accuracy.

- Deployment: I didn't have forever to built Code Assistant and to save time, I decided to only use models offered by vendors as a service. We'll leave self-hosting for another day.

- Cost: There are large differences in costs between model vendors, and if you self-host models, you have to pay for the infrastructure based on the resources used by the models.

[Artificial Analysis] is a great resource for comparing cost/performance of models and vendors. However, they don't cover embedding models, so I had to do more leg-work and collect data from vendor website, MTEB results and some experiments. Naturally, I added the results to Nile's documentation.

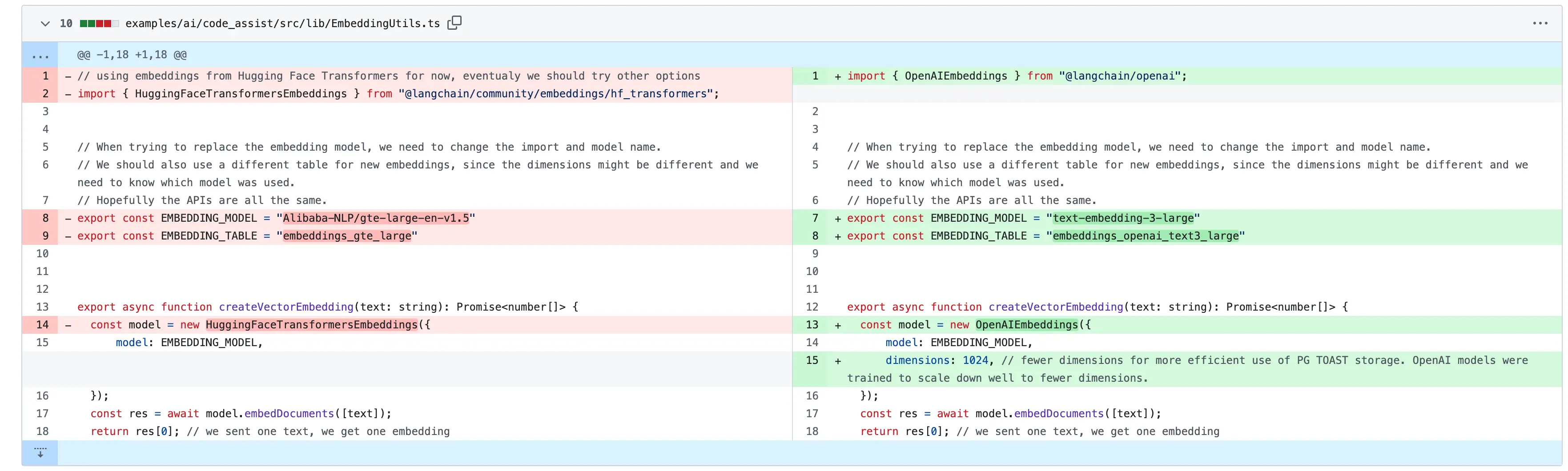

Switching models:

As I mentioned above, some models and vendors are really easy to switch up because they offer similar APIs. In particular, many vendors that offer OSS models do this with an API that is compatible with OpenAI's API. This means that you can switch between OpenAI's models and OSS models with minimal changes to your application. However, if you want to experiment with priorietary models, you may have to make more changes. I suggest wrapping the calls to "generate embeddings for document" and "generate embedding for user question", so you will have standard inputs and outputs for the rest of the application as you switch models. Otherwise you'll need to change the code in many places as one API returns an array of objects with vectors and another returns an object with an array of vectors.

I chose OpenAI's text-embedding-3-large model for the embeddings and OpenAI's gpt-4o-mini model for the conversational model. I chose them because they are good at the task, have a reasonable cost, and are easy to use. I also experimented with some OSS models, but I had issues deploying them and didn't get the performance I expected. I'll probably revisit this in the future. Because I switched between OpenAI compatible models, the changes in the code for my experiements were minimal:

If I switched to Google's Gemini APIs, which aren't compatible with OpenAI, it would have been a larger diff.

AI SDK:

If you take another look at our high level diagram, I needed an API that takes a user question and provides an informed response. This means the API handler needs to:

- Accept a question from the user

- Embed it

- Retrieves relevant documents from our database

- Calls the text generation model with the question, documents and prompt

- Respond with the answer and also with the list documents that were used to find the answer (so we can highlight them in the UI).

To put all these steps together, I decided to use LangChain. LangChain is the most popular AI SDK for Javascript, so it looked like the right choice. But I have to say that in retrospect, I am not sure I'd make the same choice.

I mentioned earlier that different models, vendors and model types have different APIs. LangChain does not mask this complexity - you import different modules and use them with different input and output structures. Some of these modules are contributed by the community and have varying quality of documentation. So, this wasn't as helpful as I hoped it would be.

In addition, LangChain's many RAG examples all looked too complex for my simple use case. I pre-embedded the documents and had no need to chunk the question, so there were no pre-processing steps. I prefer to write my own DB queries so I didn't need the SDK to act as a mini-ORM either. I just needed to call the model, which for most text generation models is a fairly simple API call.

Calling OpenAI with LangChain:

const model = new ChatOpenAI({

temperature: 0.9,

model: "gpt-4o-mini",

});

const answer = await model.invoke([

new SystemMessage(...),

new HumanMessage(...)]

);

And with OpenAI API directly:

const answer = await openai.chat.completions.create({

messages: [

{ role: "system", content: "..." },

{ role: "user", content: "..." },

],

model: "gpt-4o-mini",

});

And as I mentioned earlier, many vendors support the OpenAI API client, you just need to set a different URL and API key in the environment and that's about it.

So, while I used LangChain in my example, it would have looked very similar if I used the model vendor's APIs directly. I'll probably do that in the future until my use-cases become significantly more complex.

Ingestion phase - generating embeddings

The ingestion phase is the process of loading the source documents, splitting them into chunks, generating vector embeddings, storing them in a database, and optionally indexing the vectors.

Because ingestion isn't part of the Code Assistant user-facing flow, I could do all the work in a script, running on my laptop. This made it easy to load the data - I could clone the repositories I wanted to embed and work with local files, rather than figure out the Github APIs.

The embedding model's I've experimented with (both OSS and proprietary) all accepted at least 8K input tokens. While embedding various repositories, I discovered that most files that make up a code base are significantly smaller. 80% were under 1000 tokens, and 98% were under 2000. This is a sign of good code - files are relatively small and are also highly cohesive - containing one class or one module with tightly related functionality. Which makes them ideal as an embedding chunk. So, I ended up embedding entire files rather than breaking code into individual functions.

Embedding entire files doesn't always work well, though. I ran across iPython Notebooks code with very large files with very loosely coupled functionality for instance. Dealing with these will require more investigation into chunking libraries that are more aware of the language syntax (the usual text chunking libraries go by word count, which seems like a bad fit for chunking code).

Once I had the data and decided on embedding each file in the repository as a chunk, the code was pretty simple.

I wrapped the embedding library:

export async function createVectorEmbedding(text: string): Promise<number[]> {

const model = new OpenAIEmbeddings({

model: EMBEDDING_MODEL,

dimensions: 1024,

});

const res = await model.embedDocuments([text]);

return res[0]; // we sent one text, we get one embedding

}

As you can see, I have a single embed method for both documents and user questions, but it would have been smarter to build two separate methods,

since some models have optimizations for each task. In addition, this method doesn't batch the documents, which would be better for performance.

But the important thing is that we now have only one type of input and output to work with, which will make it easier to switch models in the future.

The next step is to use this method to embed the files and then store the results:

const client = await nile.db.connect();

await client.query("BEGIN");

try {

for (const file of files) {

const content = fs.readFileSync(file, "utf-8");

// skip files that are larger than the max-token limit of the model

if (content.length > 0 && content.length < 8192) {

const result = await nile.db.query(

// store file

`INSERT INTO file_content(tenant_id, project_id, file_name, contents)

VALUES($1, $2, $3, $4) RETURNING id`,

[tenant_id, project_id, file, content]

);

const embedding = await createVectorEmbedding(content); // embed

const formattedEmbedding = JSON.stringify(embedding);

await client.query(

// store embedding

`INSERT INTO ${EMBEDDING_TABLE}(tenant_id, file_id, embedding) VALUES($1, $2, $3)`,

[tenant_id, result.rows[0].id, formattedEmbedding]

);

}

}

} catch (error) {

await client.query("ROLLBACK");

throw error;

}

await client.query("COMMIT");

Note how we embed and store the entire repository in a single transaction. This way we don't end up with files that lack embeddings,or with a partially embedded repository. If needed, we roll back the entire operation and re-try later. Very useful while experimenting.

Conversation phase - bringing embeddings to a model

The conversation phase is the process of taking the user question, generating a vector embedding, searching the stored vectors for related chunks, and then sending the question with the related text and a creative prompt to the model. When the model responds, the question and answer are stored and displayed to the user. This is all implemented in the API handler.

Embedding the user question is straightforward, we re-used the createVectorEmbedding method from the ingestion phase.

const embedding = await createVectorEmbedding(body.question);

The next step is to find the relevant embeddings. We do this by querying the embeddings table with the user question's embedding. As I mentioned earlier, our data model allows doing this in a single query. Because we store both the embeddings and the code in the same database, we can join the two tables and search for the relevant code snippets.

const query = `

SELECT file_id, file_name, contents

FROM ${EMBEDDING_TABLE}

JOIN file_content fc ON fc.id = file_id

WHERE fc.project_id = $1

ORDER BY (embedding <#> $2)

LIMIT 5

`;

The distance metric that we used, <#> is the dot product (or inner product). This is the most efficient to calculate, but is only a good measure of similarity if the vectors are normalized.

If they are not, or you aren't sure if they are, you should use the cosine distance, <=>.

And the last step is to take the user question and the retrieved code and send it to the model.

const model = new ChatOpenAI({

model: "gpt-4o-mini",

temperature: 0.9,

});

const respStream = await model.stream([

new SystemMessage(`You are a principal software engineer, answering questions about code

projects to other software engineers.

Use the following snippets of retrieved code to answer the question.

They represent code snippets from the files most similar to the question.

Include code snippets from the provided context in your answer when relevant.

Context: ${allContent.join("\n")}`),

new HumanMessage(

`Please answer this question: ${body.question}. Helpful Answer:`

),

]);

Note that the prompt is quite extensive. I ran some experiments and was surprised how much the prompt affected the quality of the response. For example, when I told the model that it is a software engineer answering questions for other software engineers, it used more code snippets in the response. So it is worth experimenting with a bit of prompt engineering.

Now that we have the response from the model, its time to get it back to the user.

Streaming user experience

As I mentioned earlier, we wanted to show the response from the model as it was getting generated, to have the same cool UX as ChatGPT. This turned out to be the hardest part of the project.

Looking at the LangChain or OpenAI example for working with a streaming response, you see something like this:

const stream = await model.stream("Tell me a joke.");

for await (const chunk of stream) {

console.log(chunk);

}

At first glance, getting a streaming response is trivial!

On second glance - this example is printing the response to the console. I need to stream it to the browser over HTTP and then display the response in the browser.

Like most APIs, mine sent a JSON response. JSON is great, because it allowed me to have a field for the list of documents I used and a field for the response.

But, JSON is TERRIBLE for streaming. Why? Because you can't parse it until you get the last character - }. What's the point in streaming a response if I need to

wait for the last byte to parse it?

The solution involved:

- Splitting the answer into two parts - list of documents in JSON, a marker to note the start of the chat response, and the chat response.

- Using Javascript APIs to stream the response

- Using a streaming reader in React to buffer the first part of the response, parse the json, display the documents and then continuously update the chat window with the response as it continues to arrive.

Splitting the answer to parts is easy, and streaming the response from the backend is fairly straightforward too. You use an iterator and the Javascript controller API, which is quite usable:

function iteratorToStream(iterator: any, response: string) {

return new ReadableStream({

start(controller) {

controller.enqueue(response);

controller.enqueue("EOJSON"); // this is our separator.

},

async pull(controller) {

const { value, done } = await iterator.next();

if (done) {

controller.close();

} else {

controller.enqueue(value.content);

}

},

});

}

Putting things back together on the React side is more involved. First, we had to read the response and parse the different parts:

const reader = resp.body.getReader();

const decoder = new TextDecoder();

let done = false; // we need to read the stream until it's done

let partialData = ""; // accumulate the data as it comes in

let recievedFiles = false;

while (!done) {

const { value, done: doneReading } = await reader.read();

done = doneReading;

const chunkValue = decoder.decode(value);

if (!recievedFiles) {

partialData += chunkValue;

// first part of the response is json, second part is the answer

const dataParts = partialData.split("EOJSON");

if (dataParts.length > 1) {

const jsonPart = JSON.parse(dataParts[0]);

setLlmResponse(jsonPart);

// display first part of the answer

dispatch({ type: "updateAnswer", text: dataParts[1] });

recievedFiles = true;

}

} else {

// display another part of the answer

dispatch({ type: "updateAnswer", text: chunkValue });

if (done) {

dispatch({ type: "done", text: "" });

}

}

}

You see where we call dispatch ? this is where we update the chat with the on-going answer. React is kind of neat in that all dispatch does is update an array with the response and React automatically handles how to refresh the right parts of the UI to show the new answer (we copy the array in order to make React notice the change and trigger the refresh:

const conversationListCopy = [...state.messages];

const lastIndex = conversationListCopy.length - 1;

conversationListCopy[lastIndex] = {

...conversationListCopy[lastIndex],

text: conversationListCopy[lastIndex].text + action.text,

};

return {

...state,

messages: conversationListCopy,

};

If you want a longer explanation of how this all works, I went a bit deeper in our documentation. But this is pretty much it. The core of our Code Assistant right here.

Next Steps and Ideas:

Writing Code Assistant was a lot of fun. Part of the fun was balancing between my desire to complete the project and publish something - and the endless list of things I could experiment with. Here are a few things that I wanted to try and didn't get to. Contributions are always welcome!

Chunking the code into smaller parts: Perhaps individual functions. This will let us handle cases with larger or loosely coupled files. I am curious if this will improve the results over embedding entire files or degrade them. I think the best result will be to create small chunks of code, but keep references to other chunks from the same file and maybe provide the model with some of those. Lots to try here!

Different embedding models: I already discovered that GTE-large does a bit better than the OpenAI embedding model. But I’m curious about others. Google has a high ranking model. Voyage AI has a code-specific embedder with very good ranking for its size.

Different chat models: We are using OpenAI model for the conversation, but why? Everyone says that Claude is amazing. There is a code-specific version of Mistral called Codestral. So many models out there - so many experiments to run.

Store and use the questions and answers: Right now, we don't store the questions users asked or the responses we provided. But these can also be relevant data for future conversations. We can use the past conversations in 3 different ways:

- Always provide the model with last N questions.

- Embed the questions and answers and use them in a vector similarity search - so we can provide the model (or the user directly?) with the most relevant past conversations.

- Fine-tune the model with past conversations.

We'll obviously store everything in virtual tenant DBs of course - no one wants their private conversations leaked!

Feedback mechanism: Once we store the answers, we can also ask the user to tell us if they are good or not. Then, when we use past answers as context to the model, we can filter and make sure we only use the good answers. This is especially important when we use past conversations for fine-tuning. We need both good and bad examples to train the model.

But until we add all these bells an whistles, you are welcome to try out the Code Assistant, clone the repository and experiment with it. You can get a Nile account and a free database to play with by signing up to our waitlist.